By: Dave Benner

On September 17, 1787 representatives in Philadelphia signed the finalized United States Constitution. This occurred after a summer filled with contrasting proposals and rigorous debate.

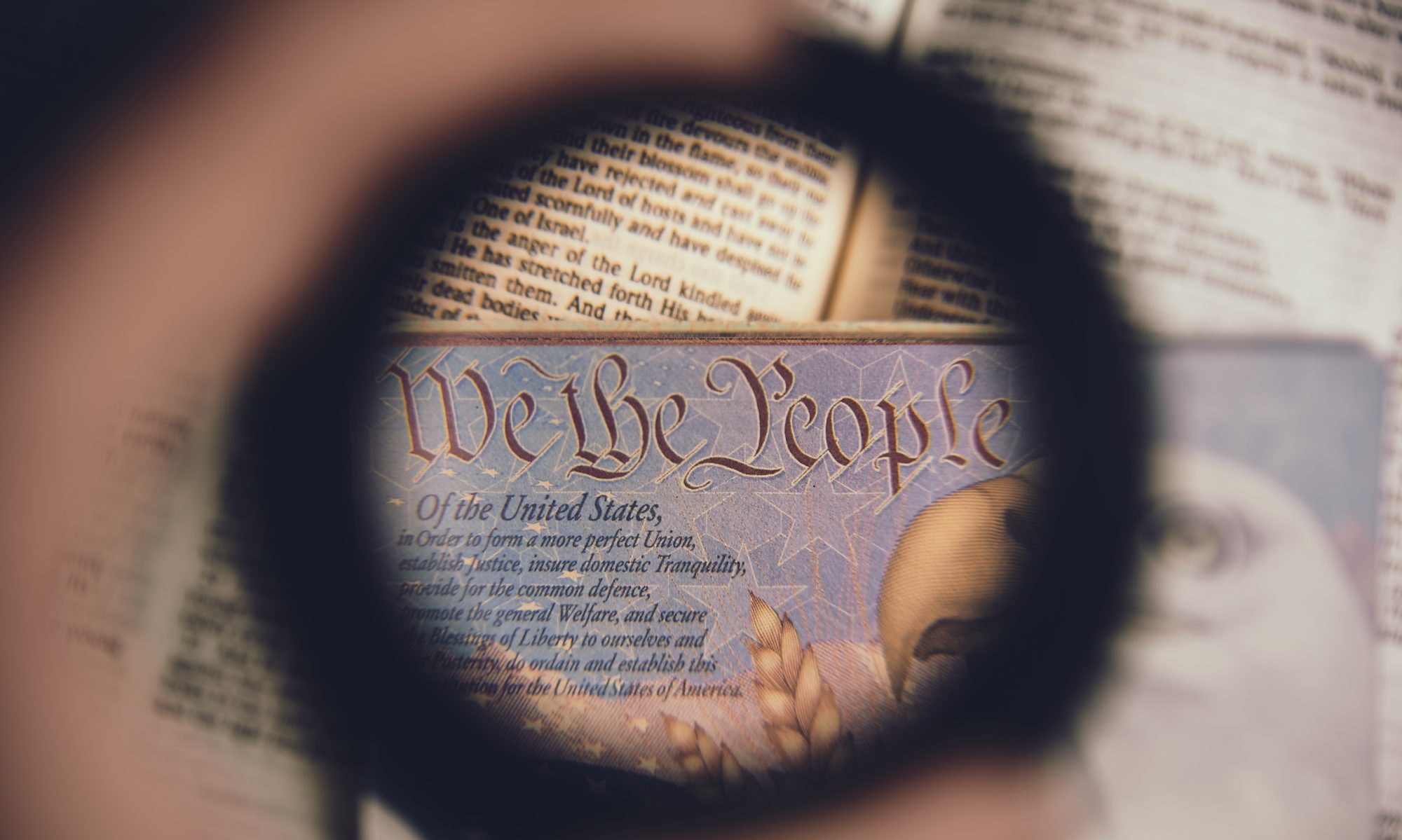

The convention decided upon a league of states rather than a national government, settling on “a more perfect union.” Throwing monarchy to the wayside, the body embraced the separation of powers doctrine, ensuring one center of power could not become too dominant over the others. The document incorporated federalist maxims, and recognized that all powers not enumerated would be reserved to the states and the people.

Some were adulated. Prominent delegates that were supportive of the final version included Roger Sherman, Oliver Wolcott, Charles Pinckney, Benjamin Franklin, James Wilson, James Iredell, Gouvernor Morris, John Rutledge, Rufus King, and John Dickinson. These individuals worked within their respective states to sell the document to the masses, declaring that all powers transferred to the general government were expressly delegated.

However, not all were so impressed. George Mason – who shunned the finalized Constitution because it lacked a bill of rights and would not allow for the elimination the international slave trade for twenty years – departed the city in disdain and refused to sign the document. “Colonel Mason left Philadelphia in an exceeding ill humor indeed,” James Madison wrote. Elbridge Gerry and Edmund Randolph also refused to sign. Two-thirds of the New York delegation had left in protest in July, and two delegates from Maryland left the proceedings as well. Many set out to dissuade their home states from ratifying the document almost immediately after the convention.

Both Madison and Alexander Hamilton, who later worked strenuously to secure ratification in their own states, were displeased by the Constitution but signed regardless. Hamilton disclosed that his ideas were “very remote” from the final version. This was a true admission – in Philadelphia Hamilton proposed a nationalist government where the executive served for life as a practical monarch, where senators served for life, where states were basically eradicated, and where the executive appointed state governors.

Madison signed the document but admitted to Thomas Jefferson that it did not suit his liking – he was especially concerned about the lack of a federal negative over state laws, the fact that all states would be equally represented by the Senate, the fact that the judiciary would be less powerful than was called for by his Virginia Plan proposal, and because the general government would be confined to enumerated powers rather than be equipped to exercise general legislative authority. Madison felt the document was superior to the Articles of Confederation, but felt it had deficiencies. Still, Madison understood that the new framework “would give to the general government every power requisite for general purposes, and leave to the States every power which might be most beneficially administered by them.”

As a woman patiently waited in front of the locked doors at the Pennsylvania State House, many were left mystified as to which type of government would be proposed. By that time, most of the western world only knew monarchy. Emerging from behind the doors, Benjamin Franklin, a man knew by the pen name of Richard Saunders approached. When asked by the woman what form the new government would take, Franklin answered astutely: “A republic, if you can keep it.”

While the Constitution was signed on this day, it had absolutely no legal effect until ratified. The ratification mechanism decided upon and articulated in Article VII called for independent state conventions to determine each state’s endorsement. As such, the Constitution was a compact “between the States, so ratifying the same,” according to Article VII. The ratification struggle continued throughout the next few years, while the document remained incredibly controversial and faced tough barriers in some of the most important states, such as New York and Virginia.